So as I was working on a problem set for 15-252 (also known as the bane of my life, devourer of my week, et cetera), I stumbled upon a very cute special case of a more general statement that I was trying to (and failing to1) prove. The statement and its proof are fairly short/clean, so I figured I could type it up both as a fun puzzle and as a way to avoid studying for my 21-268 midterm. (Update: the midterm still didn’t go as well as I’d have liked. Perhaps procrastination is not a good idea after all.)

Anyway, here’s the question for you:

How many binary strings of length \(n\) are there without any pair of consecutive zeros?

If you’d like, you can stop reading and try to come up with the answer on your own; it’s not a very long proof. Actually, I think it’s very similar to the domino tiling problem, if you’ve ever seen that one before. (Oops, I think I gave away the answer in the title.)

intuition

Anyway, I’ll first present the intuition behind the main claim. Granted, for a statement this simple I don’t think an “intuitive” exposition really adds anything, but it’s helpful for more general cases and tends to be a somewhat overlooked practice in mathematics.

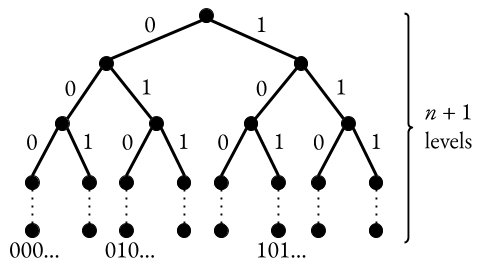

When I approached this problem, I actually thought of it graphically in terms of a tree. Consider a binary tree of depth \(n+1\), where the label the left and right edges with \(0\) and \(1\) respectively:

Then we can let each of the \(2^n\) leaf nodes (at the bottom) represent one binary string of length \(n\), based on the path used to get there from the root node (at the top). For instance, the leftmost leaf node would represent the binary string \(00 \ldots 00\), since we would need to take the path consisting of all \(0\)’s to get there. The problem now becomes one of counting the valid leaves in the tree.

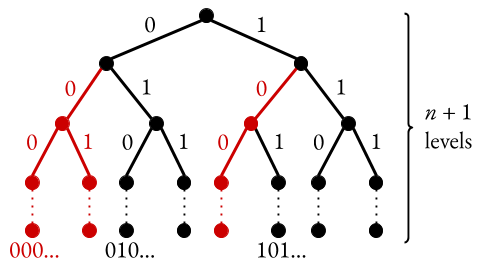

Now let’s consider the left subtree. If we go left twice, then our string will start with \(00\), which is no good. In fact, if at any point in a given path we travel left twice consecutively, the resulting subtree will be no good. Visually, we cross out all such subtrees:

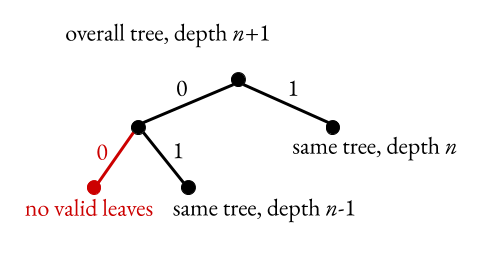

Now what’s left? Well, we could try to enumerate the nodes, but there’s actually a very beautiful recursive pattern than we could use instead. Observe that the left-left tree is absolutely no good; any leaf in that tree will not be valid. In the left-right subtree, we get a very similar picture to the overall tree, except that there are now \(n-1\) levels instead of \(n+1\) levels. Similarly, in the right subtree, we get another similar picture, this time of depth \(n\). Visually, this is to say:

So how many valid leaves are there in the overall tree of depth \(n+1\)? Well, it’s just the sum of the number of valid leaves in two “similar” trees of depths \(n\) and \(n-1\). A recursive structure? Sounds like a proof by induction to me!

more formally…

Claim: Denote \(F_n\) to be the number of \(n\)-bit binary strings without any pair of consecutive zeros. Then \(F_n\) is precisely the \((n+1)\)-th Fibonacci number2.

Proof: By strong induction on \(n \ge 0\).

- Base case: If \(n \le 1\) (i.e. the string has zero or one bits), then clearly we cannot have a pair of consecutive zeros. In this case, \(F_n\) is just the total number of \(n\)-bit binary strings, so \(F_n = 2^n\). We indeed have that \(F_0 = 1\) and \(F_1 = 2\), which are the first and second Fibonacci numbers respectively.

- Inductive step: Suppose \(n \ge 2\), and assume the claim for all \(k < n\). Now we can parition all binary strings of length \(n\) into three groups based on their prefix:

- If the string starts with \(1\), then the remaining \(n-1\) bits can be any string that does not itself contain a consecutive pair of zeros. By the inductive hypothesis, there are \(F_{n-1} = f_n\) such strings.

- If the string starts with \(01\), then the remaining \(n-2\) bits can be any string that does not itself contain a consecutive pair of zeros. By the inductive hypothesis, there are \(F_{n-2} = f_{n-1}\) such strings.

- If the string starts with \(00\), then no matter what the remaining \(n-2\) bits are, the string will not have the desired property; we’ve already found a pair of consecutive zeros in it.

Hence in total we have \(F_n = F_{n-1} + F_{n-2} = f_n + f_{n-1} = f_{n+1}\). This is the \((n+1)\)-th Fibonacci number, as claimed. ∎

In fact, it easy to see how the claim generalizes to binary strings of length \(n\) without any consecutive sequence of \(k\) zeros for any natural \(n\) and \(k\).

1 Fun fact: \(2^n = n^{n / \log_2 n}\). This is not very difficult to see, but it took me an embarrassingly long time to realize this. This is not what I was trying to prove, but it greatly simplified the bound I was trying to prove. I still didn’t manage to prove the full bound.

2 Here we take the conventional definition of the Fibonacci numbers as \(\langle f \rangle = 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, \ldots\), where we start indexing at zero. Hence we consider the zeroth Fibonacci number to be \(f_0 = 1\) and the fourth to be \(f_4 = 5\).