At this point, I have a few other (more technical) posts in the making, but I don’t feel particularly compelled to finish them right now. (You’ll probably see them appear later throughout the year. Sneak peek: topics include Free Software, the Apollo Program, and Programming Languages.) So, I’ve decided to put into writing some thoughts that have been swirling around in my head for a while; specifically, I wanted to write about the current state of high school computer science education in the US.

A fair warning: I suppose I come from a fairly “traditional” programming background: a Chinese, male teenager who likes STEM and programs computers in his spare time. As a result, it’s possible that some of the things in this post could come off as somewhat elitist, or at least one-sided. I would welcome comments from people with different perspectives on the matter; just send the comment to blog-comments@ericzheng.org. Hopefully I’ve made commenting sufficiently difficult that few complaints will come my way.

“Programming” vs. “Computer Science”

In my opinion, one huge problem with high school computer science education is the failure to adequately distinguish between programming and computer science. The two fields are definitely interconnected—for example, Knuth’s legendary1 book is titled The Art of Computer Programming—but there’s a fine difference that’s often not presented to students. In my view, programming is a practical method getting a device to do something; computer science is the abstract study of computational machines. The difference is probably comparable to that between mechanical engineering and theoretical physics: at the high school level, engineering and physics are often introduced in a very similar manner, but a professional engineer will likely have little use for general relativity2. In fact, what I’ve termed as programming here might also be called software engineering; it’s just that the former term is much more common in high school education. The difference between programming and computer science is probably narrower, as computers tend to straddle the line between application and theory, but it’s definitely there.

Why does this matter? Well, for one, it’s somewhat annoying to hear people yammering on about how much they love CS when they’ve had little if any exposure to actual computer science. But given how popular it seems to be to “major in computer science,” or be “passionate about computer science,” it might be legitimately helpful for people to realize that, often times, they’ve fallen in love with a specific application of computers, like game design, web design, or application programming, and would likely be unhappy spending four years learning about monads and functors. Especially given the current craze of “everyone should learn CS” (which I feel is misguided at best, but that’s another story), it’s important to understand exactly what we mean when we teach and learn computer science.

High school classes in the US, even if they have “computer science” in the name, are almost universally software engineering classes. They tend to focus on the specifics rather than teaching more generally applicable abstractions and analytic thought, and yet it is these things that are the most important to teach to prospective computer scientists. It’s also interesting to note that computer science education almost universally begins with procedural or object-oriented programming (e.g. CoPE). Is this a good thing? There are times when it seems to me that we might be better served starting with functional programming, which tends to focus far more on abstraction and thinking than on any specifics. (And is definitely much more mathematically “pure.”) There is some precedent: I believe that CMU used to teach some of its introductory programming courses in Scheme. (However, it seems that they have since switched to Python.)

A Purer Approach?

So, is there any hope for the high school education of “computer science” proper? To put it another way, our current courses tend to teach things “bottom-up” (i.e. starting with basic code and then introducing higher abstractions); is it possible to teach things “top-down?” To an extent, this is what the AP CS Principles curriculum tries to do. I haven’t taken that exam, but PLTW CSE was somewhat based on it. I’m basing a lot of my thoughts on my experiences in that course.

I think one big issue is that abstract thinking requires a good deal of mathematical maturity, which might be challenging at the high school level. I’m not sure if taking advanced math classes is necessarily a prerequisite for learning more abstract computer science, but the style of thinking that you develop as you’re exposed to deeper math is exactly the style of thinking you should have going into CS. For example, you likely won’t need (much) calculus in computer science, but I imagine that it would be easier to grasp the concept of higher-order functions if you’re already familiar with thinking of the differential operator as a higher-order map between a function and its derivative.

As a result, most attempts to teach a mathematically pure version of CS will inevitably feel very watered-down. As much as I loved CSE, this was definitely something that I felt could be improved. Just taking a look at the official curriculum from the Info Session slides:

Most of the items were covered pretty well; Python graphing with matplotlib was covered nicely, and cryptography was very clear without having to mess around with fancy math. But “algorithms and functional programming,” arguably the most theory-intensive item in the list, was barely touched upon, even though functional programming is extremely important for practical (e.g. parallel computing), aesthetic (it’s extremely elegant), and pedagogical (it teaches abstract thinking) reasons.

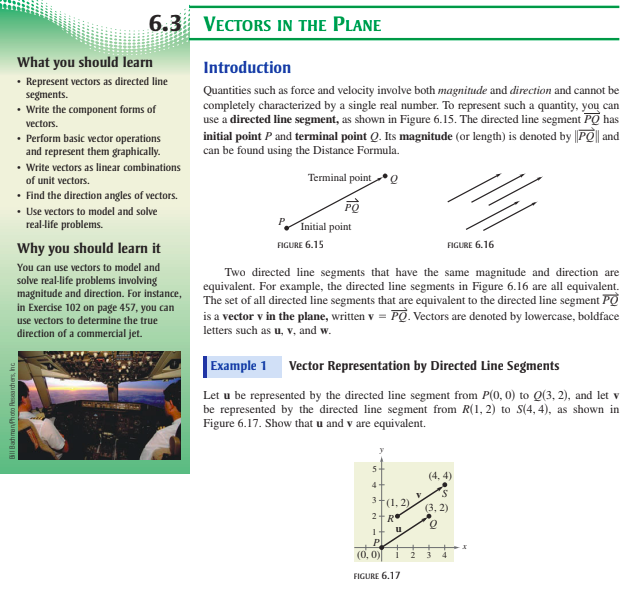

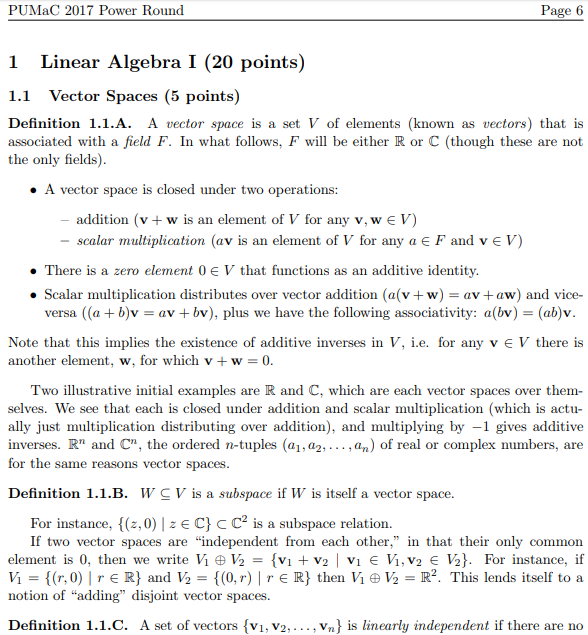

But maybe that’s not a bad thing. Consider the progression of primary and secondary school mathematics education: we start with arithmetic, go on to elementary algebra and geometry, proceed to calculus, and (time permitting) begin diving into vector calculus and linear algebra. When you were in primary school, you probably learned addition by counting on your fingers. The more theoretically “pure” approach to addition would be first presenting Peano’s Axioms and then inductively defining the elementary arithmetic operations, but it would be nearly impossible to actually learn to add this way. Or to give a perhaps more pertinent example, your first introduction to vectors was probably as arrows in 2D geometry, not as the study of elements in a vector space closed under certain operations.

Take a look at the above two introductions to vectors. Granted, they are meant for different purposes, but the differences in the barrier to understanding for the simple, practical approach (left, Precalculus with Limits by Larson) and the abstract, theoretical approach (right, PuMAC Power Round 2017) are immediately evident. From an mathematical standpoint, the right-hand approach may be more “pure,” but the left-hand approach is likely more educationally sound.

In the nineteenth century, physics was composed of several branches: classical mechanics, electromagnetism, thermodynamics, etc. We began with a basic understanding of these fields; gradually, as our knowledge grew, we began to realize the deeper, underlying connections between them, such as how much of thermodynamic behavior follows from statistical mechanics. These days, we’re on the hunt for a “theory of everything”—a great framework within which all of our previous observations can be abstracted to make sense. Maybe a student’s knowledge of computer science should grow “organically” in much the same way: gradually uncovering a deeper meaning rather than focusing on sheer rigor.

Summary and Conclusion

To summarize:

- Programming is not necessarily the same as computer science, and it would probably be in our educational best interests to make that distinction earlier. As an example, the attrition rate for computer/information science majors is around 60% (2013 NCES STEM Attrition Study, page 14). Perhaps this would go down if more high school students had a clearer conception of what computer science study really entails.

- There’s sort of an inherent friction between presenting computer science “bottom-up” and “top-down,” with the latter being more mathematically abstract but more difficult to understand.

This isn’t a new debate, and the more I think about it, the more I think it’s really a matter of perspective. For someone who comes from a strong programming background, it feels almost natural to look at, for instance, the AP Computer Science A curriculum and (if you’ll excuse the arrogance) feel that it’s far too trivial. When we see a loop, there’s an immediate temptation to jump right to recursion (which is used instead of looping in functional languages) as the “abstract” way to frame the problem, but we often forget that we ourselves would have found that explanation difficult to swallow when for and while loops were new to us.

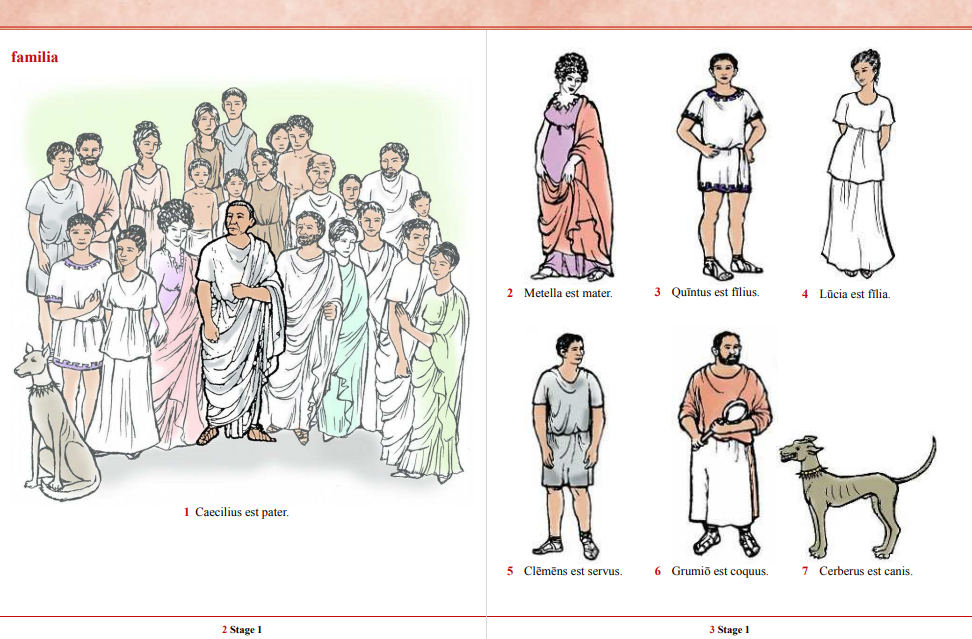

The question of how to best structure education is, naturally, not exclusive to computer science. There’s a similarity between a classic debate in the history of mathematics between intuition and rigor. Honestly, you could even link it to the debate in Latin education between the “grammar-translation” method and the reading-based method. If you know anyone who took Latin back in the 1950s, chances are they first memorized tables upon tables of grammatical forms without knowing what any of them meant. The emphasis was on rigorous and thorough knowledge of the underlying grammar—only after grammar was mastered could the language be really understood. From the perspective of a professor who has known the basic conjugation tables for years, this seems to be the most “correct” approach. Wheelock’s Latin is an example of a textbook known for this method.

Yet educational theory has shifted since then, and we now use the Cambridge Latin Course instead (sorry, I couldn’t help but link to my own website). Instead of formal exposition on the various forms of Latin grammar, the book starts off with simple cartoons and easy sentences. There are stories, but the focus is on reading comprehension, not fussing over the exact form of a verb. Compare the first page of Cambridge (left) with that of Wheelock’s (right):

Latin has been having this debate for centuries. The past half-century of debate in computer science education has really just been a warm-up.

Footnotes

1To give an idea of just how ridiculously thorough this book is, consider that Donald Knuth, perhaps the greatest computer scientist currently alive, has been working on it since the 1960s and isn’t done yet. The coding examples are given in a hypothetical constructed assembly language. To quote Bill Gates: “You should definitely send me a resume if you can read the whole thing.” That’s not to say, of course, that you should work for the enemy Microsoft.

2Funny I should say that; this leads into a wonderful bit of trivia. We often take GPS for granted, but it’s actually an extremely complex system. I’ve heard it said that GPS satellites are just about the only engineering application in which we have to account for both special and general relativity for things to work.

Oh yeah, as usual, the pictures in this post are mine, but the images may contain copyrighted content. So I don’t really care what you do with them.

Supplemental Reading

This is somewhat tangentially related to the above post, but I felt that this difference in how we view computers is at least partly cultural, by which I am referring to the computer “user” culture (perhaps epitomized by Microsoft Windows) and the computer “programmer” culture (perhaps epitomized by the Linux project). This post is veering on incomprehensible wall of text, so I won’t go into further discussion here, but there are two brilliant essays on this floating around on the Internet: here and here, if you’re interested.

Comments

(Here’s what I’ve received via email.)

Comment #1 Elijah Thorpe, 10/20/18 1:12 PM

I agree with you that it is annoying that no one keeps the difference between CS and programming constant. After spending awhile worrying about choosing the major that I actually want (a programming major, not a math major), I just gave up and decided to go with an engineering major that has an emphasis on programming.